Git is the TV of the computational living room: all the furniture is pointing at it. However, as a biologist, I have been struggling on how to integrate my biological approach into my Git workflow.

I was reading some git best practices. The first point was on the importance of using branches to develop new features so that the master branch remains clean and functional. My thoughts derived from that idea and I suddenly understood what branching could mean in the context of biological data analysis.

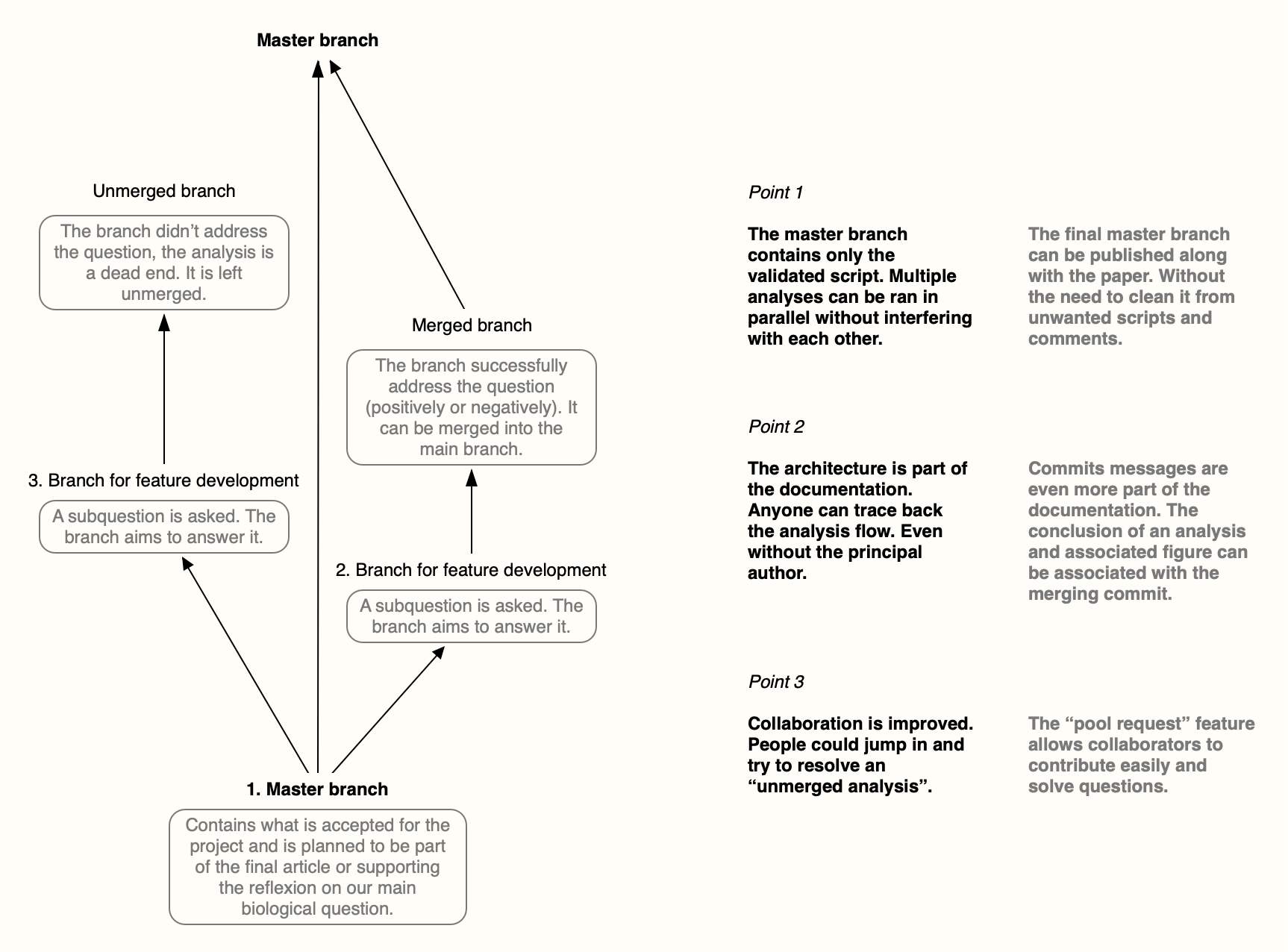

The main concept is to shift the perspective from software development to biological investigation / data analysis. We reuse the same commands of Git, there is no wrapper or anything. We just translate the meaning of the concepts that git manipulates. So … in practice, it’s only a matter of perspective.

The master branch

The master branch starts with what is necessary for your analysis, and is not specific to a biological hypothesis you are testing.

For instance, in R, I could be loading libraries and datasets, and pre-process my data.

Branching

To address a biological question, create a new branch which title is somehow representative of the biological hypothesis you wish to test.

For instance, if I wanted to check if two different genotypes present differential gene expression, I could create a branch called DGE.genotype (check the possible git branch nomenclature, because the ? character is not allowed for example) and run my analyses in that branch.

Merging branches

When a question/hypothesis is being addressed:

- Either the analyses led to insightful results, in that case you can merge the branch into the master

- Either the analyses are inconclusive and you don’t need to clutter the master branch

When in situation (1), summarise the conclusions of the analyses in the merge commit message.

I would still recommend not to track documents that can be generated from script, such as the figures or tables. Instead, I would provide their name in the merging commit message.

Example of multiline merge commit message:

Merge DGE genotype:

* Q: Does the genotype influence the gene expression?

* R1: KO samples show higher oxydative stress and cell-cycle genes

* R2: Cluster 5 is CD74 high only for KO

* table: name_of_the_table.tsv

* figures: name_of_the_figure1.pdf, name_of_the_figure2.pdf

Situation (2) does not prevent from writing insightful last commit about the reason why a branch is not merged and ideas on further analyses that could address the problem.

Discussion

How is it better?

Before, I was just doing everything linearly and not using the branching command of Git. I was retaining every line of code that merely led somewhere and I was commenting how useful it is for any conclusions I reached or parameter I used. Once analyses were considered done, after several months of ponctual additions and modifications, I ended up with a script of hundreds if not a thousand lines that I needed to trim to extract the parts relevant for the construction of the article’s argumentary. I also relied much more on in-line comments to document figures exported from the code and ended up questioning the use of Git for a solo script development.

Making (full) use of Git commands

With this new perspective, I layer the concepts I already manipulate and map them onto git features. My conclusive comments in the code are now part of the commits messages. Unused script, analytical dead ends or not validated by my PI for instance, are not part of my master branch and remain unmerged; while being accessible for other collaborators (colleagues or beyond) to contribute by a pull request.

For a better computational lab notebook

With this approach, the architecture of the commits log is – itself – a part of the documentation. At a glance, one can see how many questions were addressed, what are their conclusions and which document to refer to. One can even use the host webpage (Github.com for instance) and use the drop-down menu to scroll through the branches to see the questions addressed.

This computational lab notebook is now closer to the traditional sections of a classical lab notebook. Hypothesis (a branch), method (the script and its internal comments), results (figure reference in the commit message) and conclusions (commit message and branch being merged or not) have now clearly distinct ways to be conveyed; a knowledgeable reader can find them quickly.

Easing reproducibility and collaboration

This new perspective compartimentalise and computationally individualise the questions. Even after merging them in the master branch, the questions are similar to integrated modules that are independent from each other. The same way software developers add features, data analysts add conclusions to their project. It makes (self-)reproducibility easier and mistakes less likely to happen because previous analyses objects are not interfering with the current analysis. An important point for me was to be able to quickly find the code behind a specific figure, and the parameters that were used to generate that figure. Mentionning the figure name in the commit message allows to easily associate code and figure.

The code is also easier to share for publication because the master script contains only the relevant information used to draw the conclusions mentioned in the publication. There is no need to spend time creating a clean version of the script for people to understand your code.

The compartimentalisation of the questions into branches makes it easier for collaborators to jump in and contribute on specific points. For instance, they can make their own branch and, once solved, send a pull request to fix your branch that you can then merge with the master branch along with your conclusive commit.

Improving focus and promoting hypothesis-driven science

Instead of randomly exploring a dataset, the git commit architecture is now centered on the hypothesis-driven research. Entering a branch, the biologist is then focused on addressing a particular question.

Is it compatible with the traditional idea of Git?

Usual commits aim to add new functions, fix bugs, optimise code, diversify the portability, and more. Is that kind of approach compatible with that new perspective?

I would think so, yes. The reason is that the branching structure and some key commits only are changed with this new approach. A branch, instead of being a new feature in development, is a biological hypothesis being addressed. The merging commit gathers the critical information. Any commit in between can be used to focus on the technical aspects necessary to address the question.

I did not yet implement the ideas of this post; time will tell if it’s a good idea.

Acknowledgments

- The illustrative diagram was generated with Scapple.

- Link to the Git best practices I was reading.

TL;DR

A git branch is a hypothesis you wish to test, merge it with the master branch only if you could reach a conclusion (biologically positive or negative); leave it as a dead-end otherwise. Document extensively the merging commits with the conclusions draw and reference to any output generated.

Have a look at the figure associated with this post, it’s also self-explanatory.